19 Alpha Rho Men Now Featured in MLK Chapel Hall of Honor Oil Portrait Gallery at Morehouse College

- Oct 10, 2022

- 33 min read

By APCAA Staff

In recognition of the Martin Luther King, Jr. International Chapel's Rededication and the 37th MLK College of Ministers & Laity Program on October 12-13, 2022, the APCAA has assembled a historical tribute to the 19 Alpha Rho-related Morehouse Men who are now featured in portraiture on the hallowed walls of the redesigned International Hall of Honor Oil Portrait Gallery. Dean of the Chapel, Dr. Lawrence Edward Carter, began the collection of the global dignitaries soon after his investiture and the opening of "The Great Knave" in 1979.

This biological reference guide represents the first-known public research publication for any of the 200+ global leaders featured in the expansive gallery. And for an Alpha Rho Chapter Alumnus -- it carries extra special significance, as the installment resides inside of the most significant edifice dedicated in honor of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., our esteemed Morehouse College Brother (c/o 1948) and Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. Brother (Sigma Chapter, June 22, 1952).

Today, Morehouse College’s International Hall of Honor consists of more than two-hundred original oil portraits of distinguished leaders in the civil and human rights nonviolent movement globally. The portraits by artists Ho Eun Chung and Dwayne Mitchell are valued at more than $900,000.

The Martin Luther King Jr. International Chapel is the spiritual center of the campus. The Chapel is dedicated to empowering transformational, nonviolent ambassadors of peace working to reveal and create the “Beloved” world spirtitual, economic, and cultural community as a reflection of the social justice of Jesus Christ. It inspires the men of Morehouse to become servant scholars and advocates for the communities. And it is home to some of the college’s signature events, like Crown Forum, as well as the historical center of the college with the writings of Martin Luther King Jr. and the history of college through its presidents and distinguished guests.

Of the 19 Alpha Rho Chapter Men now featured in the portrait gallery, there are three former Presidents of Morehouse College, eight ordained ministers, three Morehouse College Professors Emeritus, three former members of the Morehouse College Board of Trustees, a Founding Dean of the Morehouse School of Medicine, and a former United States Presidential Cabinet member (President George H.W. Bush's administration).

Complete biographies and additional images of the 19 Alpha Rho Men are provided below:

Theodore Martin ALEXANDER, Sr. — Fall 1929

A pioneering businessman, know as "Mr. Insurance," T.M. Alexander, Sr. was a leader in the Atlanta insurance industry and community activities for more than 50 years. In 1931 he created Alexander & Co (with $100 in savings), an Atlanta insurance brokerage firm that eventually became the oldest black firm in the city and one of the most successful. He managed Alexander & Co for nearly 60 years and had a roster of clients including Coca-Cola, and the City of Atlanta. He later established the Southeastern Fidelity Fire and Casualty Company in 1951 and served as Executive Vice President and Managing Officer until the company was prematurely sold in 1967.

Southeastern Fidelity Company provided more than $50,000,000 of property protection for its client groups, and was the first Black-owned multi-line insurance company. Recognizing the absence of Black representation in electoral politics in both the City of Atlanta and the State of Georgia for more than 90 years, Alexander embarked upon an ambitious effort and ran for the office of City Alderman in 1957 and for the State Senate in 1961. Although unsuccessful in each of these bids, his actions provided the motivation for other Blacks to become involved in seeking election of public office, thus paving the foundation for not only the first elected Mayor of the City of Atlanta, but also for numerous other elected positions throughout the South.

In addition to serving as the President of his insurance agency, he served as an Adjunct Professor of Insurance at Howard University, Washington, D.C., the boards of Morehouse College and the Atlanta University Center. co-founded the Atlanta Negro Voters League in 1937; obtained insurance for vehicles during the 1955-1956 Montgomery bus boycott; served as a longtime member of the Morehouse College Board of Trustees. In 1970, he was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Laws degree by Morehouse. Over the years, he has remained a pillar of the community and has assisted numerous other Blacks in gaining responsible positions in both the private and public sectors. Alexander also was an active participant in many professional and other organizations. He was preceded in death by his first wife Dorothy and a son T.M. Alexander, Jr. Alexander died at age 92. (Curtis Jackson)

Hortenius Irvine CHENAULT — Fall 1930

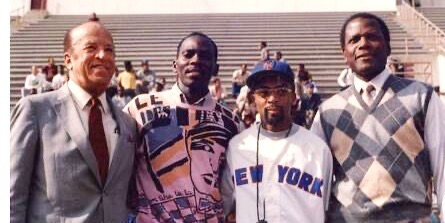

Hortenius Chenault (at right) was born in Richmond, KY, his family later moved to Mount Healthy, Ohio. He was a graduate of Morehouse College and a 1939 graduate from Howard University Dental School. Dr. Chenault passed the New York State dental exam with the highest score to date. He received a Guggenheim Award and did postgraduate work in children's dentistry. From 1939-1987, his dental practice was located in Hempstead, Long Island, in New York. He was the husband of the former Anne Quick and the father of four, including Kenneth I. Chenault, who was named Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of American Express Company in 2001. Kenneth is also a benefactor for Morehouse College, having funded the Experiential Learning and Interdisciplinary Studies and Hortenius I. Chenault Endowed Professorship. Dr. Kinnis Gosha, Morehouse College’s Division Chair, developed courses for the program that prepares students to compete for internships and jobs at top technology firms.

In addition to the gift for Dr. Kinnis Gosha's endowed Morehouse Professorship, Kenneth Chenault has also provided a generous gift to the Morehouse Cultural Heritage Preservation and Digital Humanities Initiative, co-founded by Dr. Clarissa Myrick-Harris and Dr. Karcheik Sims-Alvarado. That gift is currently supporting the Chenault-Quick Family History Research Project, Public History student scholarships, and the creation of an art installation for the Atlanta Student Movement Initiative.

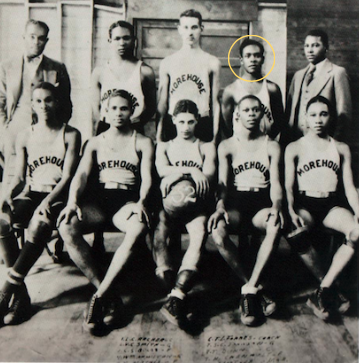

As featured in the 1932 Maroon Tiger (Torch Yearbook), during his undergrad years at Morehouse College, Dr. Chenault was a member of the college track and basketball teams, a member of the Science & Mathematics Club, and the legendary "M" Club.

Hortenius Chenault died on Monday (December 17, 1990) at his home in Hempstead, L.I. He was 80 years old. He was survived by his wife, three sons, Kenneth, of New York City, Arthur, of Great Neck, L.I., and Stephan, of Brooklyn; and a daughter, Patricia, of Hempstead, L.I.

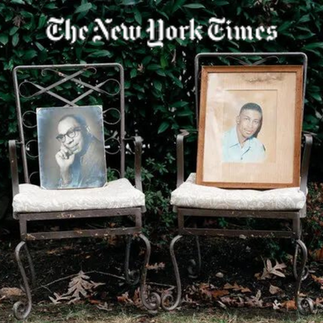

Kenneth Chenault commissioned the portrait of father and son which now hangs in the MLK International Chapel at Morehouse College. (New York Times, Notable Kentucky African Americans Database, and Chenault Family Attributions)

Hugh Morris GLOSTER, Sr. — Fall 1930

Born on May 11, 1911 in Brownsville, Tennessee, Dr. Hugh Gloster was best known as the longtime president of Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia and a literary critic. He was the seventh president of Morehouse College, responsible for establishing the Morehouse School of Medicine and the international studies program. Gloster was was the youngest child of John and Dora Gloster. He was the product of a long tradition of striving for educational excellence that led to the presidency of Morehouse College and other noted educational accomplishments.

Gloster earned an undergraduate degree from Morehouse College in 1931 and pursued graduate study at Atlanta University and New York University culminating in the doctorate degree in 1943.

His long and illustrious career at Morehouse began in 1967 when he embarked on his twenty year tenure as president of the College. Before moving to Morehouse, Gloster taught at LeMoyne College in Memphis, Tennessee where he taught from 1933 to 1941, and continued at Hampton Institute (1946–1967). Gloster was chosen as Morehouse's next president by Benjamin Mays, the previous president, with the agreement of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., then on the board of trustees. He was the first alumnus president of Morehouse College.

During his Morehouse presidency, eight new major fields of study were established and the Dual-Degree Engineering Program with the Georgia Institute of Technology was initiated. The number of faculty members and faculty salaries were more than doubled, and the percentage of faculty Ph.D. degree-holders increased to more than 65 percent. After retiring he served on the Morehouse College Board of Trustees until his death.

Student enrollment more than doubled concurrently with the establishment of higher standards for admission. Dr. Gloster was a prodigious fundraiser and led two capital campaigns during his 20-year tenure as President of Morehouse. The results of those efforts included establishing seven endowed academic chairs, quadrupling the endowment to $29 million, acquiring 30 acres of land adjacent to the campus, and constructing 12 new facilities with a combined value of $30 million. Dr. Gloster's presidency was characterized by an absence of operating deficits during the 1970s and 1980s.

In 1986, he was selected by his peers as "One of the 100 Most Effective College Presidents in the United States." More recently, he was recognized for his lifetime accomplishments by New York University (Distinguished Alumni Award, March 2001) and by LeMoyne-Owen College (MAGIC HANDS Award, May 2001). He was a prolific writer and lecturer. Dr. Gloster held honorary doctorates from Emory University, Hampton University, LeMoyne-Owen College, Mercer University, Morehouse College, the Morehouse School of Medicine, Morgan State University, New York University, St. Paul's College, the University of Haiti, Washington University and Wayne State University.

Dr. Gloster, a member of Sigma Pi Phi and Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternities, was a founding member of the College Language Association (CLA) in 1937. Negro Voices in American Fiction, his pioneering work in black literary criticism, was published in 1948. Following retirement from Morehouse, Gloster served as a consultant to the Southern Association for the Accreditation of Schools and Colleges.

Dr. Hugh Gloster died on February 16, 2002 in Decatur, Georgia at the age of 90. (www.blackpast.org, Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library, and www.dailypress.com)

William Vincent GUY — Fall 1953

Rev. Dr. William Vincent Guy (1971-2007) was the fifth Pastor of historic Friendship Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia. The church held their last service on Mitchell Street on May 25, 2014, with Rev. Dr. William V. Guy, Pastor Emeritus, delivering the sermon. Rev. Guy acknowledged the deep nostalgia that comes with the Mitchell site being home for so many decades, the even deeper sadness at the demolition of a home to which they will not be able to return, and also the challenges that come with change. He emphasized, however, that the church, the community, the people have their physical and spiritual strength. They have the passion of their convictions. They will continue to endure and to sustain their commitments to community, community leadership, and civic engagement — and so they have.

While a new sanctuary was under construction at their new site at 80 Walnut Street, the congregation held temporary services at Morehouse College in the Martin Luther King, Jr. Chapel. Two years later, with construction completed, Friendship held its first worship service at its new site on July 30, 2017.

Brother Guy is the father of noted actor Jasmine Guy and dancer Monica Guy. (www.fbcatlanta.org)

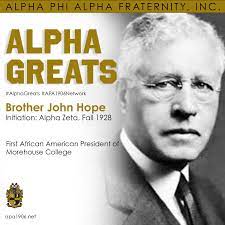

John HOPE — Eta Lambda

John Hope (1868—1936) born poor in Augusta, Georgia, became the first self-identified African-American president of Morehouse College in Atlanta in 1906 after joining the faculty in 1898. Hope graduated from Brown University, with a B.A. in philosophy in 1894 (Davis, L. 1998). Hope did graduate work for a PhD. in classics from the University of Chicago but never finished due to his responsibilities as a professor at Morehouse College. John Hope received an honorary master's degree from Brown University and an honorary PhD. from Howard University in 1920 (Davis, L. 1998).

Publicly, John Hope was uncomfortable with his title of “Doctor” and preferred to be called simply “John Hope” (Davis, L. 1998). Privately, he was happy to receive the degree and told his friend Jesse Moorland that “it came at the right time” (Davis, L. 1998). Mr. Hope held many memberships in different organizations. He was a charter member of the Atlanta chapter of Sigma Pi Phi Fraternity, Inc (Kappa Boulé, 1920), and a member of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. (Eta Lambda, 1923) (Davis, L. 1998).

John Hope had “A clashing of the soul” when it came to his racial identity. Hope was born in a racial union between James Hope (White Father) and Marry Francis Butts (Black Mother). Hope was given multiple chances to “pass” but he refused because he had pride in his race (Davis, L. 1998). For example, Hope wanted to join a white fraternity at Brown University but was told that they would only initiate him if he chose to pass and he declined. When James Hope died, the New York Hope family (White) chose to cut all funds and ties with the Georgia Hope family (Black), which lead John Hope and his siblings to grow up poor (Davis, L. 1998).

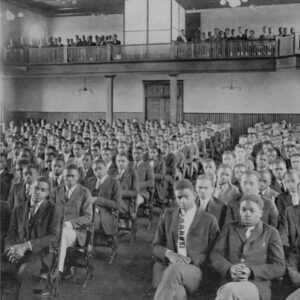

At Morehouse College, John Hope was a tough president and had very strict rules. These strict rules were adopted from his experiences at Worcester Academy and Brown University. Hope’s best friend W.E.B Du Bois was the one who convinced him to ease up on his strict rules because it restrained what was essential for college life (Jones, E. 1967). Additionally, Hope introduced a difficult liberal arts curriculum to Morehouse. Chapel (crown forum) was every day (Monday-Friday) from 9:30 am until 10:00 am (Jones, E. 1967). The most interesting thing was that “no man” could get a degree from the college until he had convinced and memorized an original oration (Jones, E. 1967). Students were required to write one each year for four years and were not permitted to graduate until they gave their oration in front of the student's body, faculty, and staff. Hope also introduced the sport of Football to Morehouse (Davis, L. 1998).

Hope was married to Lugenia Burns Hope, a social reformer who was a founder of the Neighborhood Union and played a crucial part in the founding of Booker T. Washington High School (1924) (Davis, L. 1998). Lastly, John Hope died from pneumonia on the campus of Spelman College in 1936. John Hope died the day after his wife’s birthday. One of his last words was “If only I could tell my successor what I Was trying to do ….. there is much work left to be done” (Davis, L. 1998). Hope served three decades as president of Morehouse College.

John Hope’s early life contributes much to an understanding not only of racial identity but also of class, color, and caste among African Americans, especially in the South. Born of a biracial union in Augusta on June 2, 1868, he belonged to a small Black elite whose history predated the end of slavery. His father, Scottish-born James Hope, immigrated to New York City early in the nineteenth century and eventually moved to Augusta, where he became a prominent businessman. His mother, Mary Frances Butts, was a free African American woman born in Hancock County. Although Georgia law prohibited interracial marriages, Hope’s parents lived openly as husband and wife until his father’s death in 1876.

The elder Hope’s death marked a watershed in his eight-year-old son’s life. The executors of the elder Hope’s estate failed to carry out his plans to provide a secure financial future for his family. After his father’s death, Hope’s position as a member of the Black elite stemmed not from belonging to a household with a wealthy white head but from his heritage of pre–Civil War (1861-65) free Black ancestry.

Hope’s education prepared him for his life’s work. Though he quit school after the eighth grade to help his struggling family survive, he decided five years later to complete his education and attended a preparatory school in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1886. He went on to earn a B.A. degree in 1894 at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. Hope eventually decided to become a professional educator, teaching first at Roger Williams University, a small Black liberal-arts school on the outskirts of Nashville, Tennessee.

Hope and his wife moved in 1898 to Atlanta, where he took a teaching position at Atlanta Baptist College, which became Morehouse College in 1913. It was in Atlanta that Hope first met and befriended prominent Black leaders and educators like Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois. In 1906 he assumed the presidency of the college and remained in that position until 1929, when he moved to the presidency of Atlanta University.

Under his leadership, Atlanta University became the first college in the nation to focus exclusively on graduate education for African American students. As a race leader, Hope was steadfast in his support of public education, adequate housing, health care, job opportunities, and recreational facilities for Blacks in Atlanta and across the nation. He also supported full civil rights in the South during an era when African Americans were expected to accommodate a system of inequality.

Hope faced many dilemmas throughout his adult life. Most vexing was his attempt to balance the demands of his job as president of a Black college with his role as a national leader committed to a program of full civil rights. Hope was somewhat reluctant to give up good faculty and administrators who went on to serve in such organizations as the NAACP. He frequently contemplated leaving Morehouse and becoming a professional race leader himself, pondering, though ultimately rejecting, offers from the NAACP, the Urban League, and the National Council of the YMCA.

His deep involvement in race matters often strained his relationship with the prominent white liberals and philanthropists who were influential in the continuing development of Black higher education, especially after the death of Booker T. Washington. Yet in spite of these difficulties, Hope was as influential in the development of African American college education as Washington had been in the development of African American vocational education.

Hope died of pneumonia in 1936 at the age of sixty-seven. His papers are held at the Robert W. Woodruff Library at the Atlanta University Center. (www.umich.edu and Atlanta University Center, Robert W. Woodruff Library Archives)

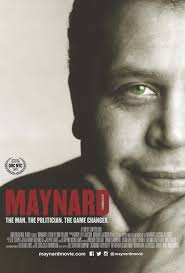

Maynard Holbrook JACKSON, Jr. — Spring 1956

The 54th and 56th Mayor of Atlanta, Social Reformer. A respected politician and political giant who became the first African-American mayor of Atlanta, Georgia in 1974, the second longest-serving mayor in Atlanta history (after William B. Hartsfield) and one of its most charismatic civic leaders. Maynard Holbrook Jackson Jr. was born in Dallas, Texas in 1938. He later moved with his family to Atlanta in 1945, where he became the minister of Atlanta's Friendship Baptist Church.

A child prodigy who entered Morehouse College at age 14, he graduated at age 18 in 1956 and struggled at Boston University Law School before dropping out. He then worked as an unemployment claims examiner, sold encyclopedias, then enrolled at North Carolina Central University Law School in Durham in 1961. Graduating Cum laude in 1964, his political star ascended in 1968 with an unsuccessful run for the United States Senate against Sen. Herman Talmadge of Georgia.

He was later elected the first African-American vice mayor of Atlanta in 1969 and then mayor of Atlanta at the age of 35 in 1973, launching him on a quarter century of political leadership, promising to build "a city of love." He was sworn on January 7, 1974, serving two four year terms. Maynard Jackson's impact as mayor was monumental to the city.

He is best remembered among other things for being the architect in the late 1970s for the expanded Hartsfield Atlanta International Airport (providing many jobs in the process), fighting for economic opportunity for African-Americans, for developing Atlanta's rapid rail system called MARTA (Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority), and giving voice to intown neighborhoods and establishing a cultural affairs department.

In the eight years after leaving office in 1982, he worked as a bond attorney before being re-elected again as Mayor in 1989. During his final term from 1990 to 1994, he became a prominent spokesman for American cities, serving as president of the National Conference of Democratic Mayors and of the national Black Caucus of Local Elected officials. He was also involved in the early planning for the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta. He later decided not to seek re-election in 1993 for personal reasons; ending his term in 1994. Maynard Jackson's accomplishments continued after leaving office, becoming chairman and chief executive officer of Jackson Securities Inc. (an investment firm).

In 2001, he made an unsuccessful bid to become president of the Democratic National Committee. His funeral in Atlanta was attended by thousands and he was remembered as one of the greatest men to occupy the seat of mayor of Atlanta, because in the estimation of many he helped bring the city to another level and made it a better place. Four months after his death, the William B. Hartsfield Atlanta International Airport was renamed: Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport (ATL) in October 2003, honoring both Atlanta mayors. (Curtis Jackson)

Hamilton Earl HOLMES — Fall 1960 (*to be dedicated in January 2024)

Dr. Hamilton E. Holmes, whose single-minded walk through the gates of the University of Georgia in 1961 tipped the state from racial segregation toward integration, died Thursday in his Atlanta home at age 54.

Holmes, the head of orthopedic surgery at Grady Memorial Hospital and an assistant professor at Emory School of Medicine, had seemed to be recovering well from a quadruple coronary bypass operation he underwent two weeks ago, but he was found dead in his bed, said his brother Gary Holmes.

Two decades after enduring jeers and isolation on the Athens campus, Holmes overcame his quiet bitterness to become a spirited Georgia Bulldog fan, recalled PBS correspondent Charlayne Hunter-Gault, the other black student who integrated UGA under a federal court order on Jan. 6, 1961. Hunter-Gault, who described their relationship as that of siblings "joined at the historical hip," said she found Holmes in the 1980s sporting a Bulldog hat and bumper sticker and reciting UGA football statistics.

"I said, 'Hamp, what happened?' 'Well,' he said, 'things change.' "UGA President Charles Knapp said Holmes reconciled with the university about 10 years ago when he helped establish the Holmes-Hunter Lecture Series and began serving as a trustee of the UGA Foundation. His son Hamilton "Chip" Holmes Jr. later enrolled and graduated there. Knapp recalled an emotional evening on campus last summer when the elder Holmes talked to a group of students about his experiences. "He was almost in tears, not of anger but of a kind of nostalgia."

Holmes and Charlayne Hunter, both of the Class of '59 from Atlanta's Turner High School, were chosen for their historic roles by local NAACP lawyers. Good-looking, bright and well-dressed, they were considered "perfectly cast," wrote Calvin Trillin in "An Education in Georgia."

Holmes also had pedigree. His grandfather, Dr. Hamilton Mayo Holmes, had been a prominent black Atlanta physician and role model. His father, Alfred "Tup" Holmes, was a businessman who won a U.S. Supreme Court case desegregating Atlanta's public golf courses in 1956, one of which bears his name. His mother, a tennis champion, came from a prominent family involved in Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

"Doc was a prince of a gentleman," Atlanta City Council President Marvin Arrington said of his lifelong friend and high school classmate. "He was the smartest man I ever met in my life." Elected Phi Beta Kappa at UGA, "he knocked the end off the curve," Knapp said of Holmes.

While Hunter struggled for acceptance on campus, she said, Holmes found his outlet off campus, playing basketball with the Athens "brothers." “He was going to the University of Georgia for one reason and one reason alone, and that was to get access to the best facilities available for becoming a doctor. It was almost like a job.” (Atlanta Journal-Constitution, October 28, 1995)

*As part of the Centennial Celebration of Alpha Rho Chapter, the Alumni Brotherhood has pledged to commission the oil portrait in honor of the late Dr. Hamilton Earl Holmes (Alpha Rho Fall 1960). The painting will be dedicated as part of their Centennial Week Celebration, January 5-7, 2024.

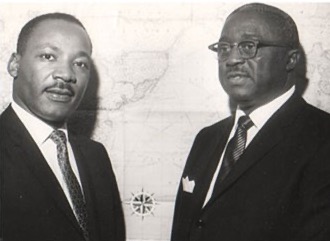

Samuel Berry McKINNEY — Fall 1947

Born on December 28, 1926 to Reverend Wade Hampton McKinney and Ruth Berry McKinney in Flint, Michigan, Samuel Berry McKinney would become a Baptist minister, author, and civil rightsadvocate in Seattle, Washington. He served as pastor of Mount Zion Baptist Church, one of the largest and oldest black churches in the Pacific Northwest, from 1958 to 1998 and again from 2005 to 2008.

As a child in Cleveland, Ohio McKinney was shaped by his father who challenged racism, and invited civil rights leaders such as Thurgood Marshall to speak frequently at his church. McKinney attended Morehouse College with the intention of becoming a civil rights lawyer, but changed paths after encountering Morehouse President Benjamin Mays who encouraged him to become a minister. McKinney, a classmate of Martin Luther King, graduated from Morehouse in 1949 and enrolled in New York‘s Colgate Rochester Divinity School, graduating in 1952.

He arrived at Mt. Zion in 1958, beginning an activist ministry that transformed the church and Seattle. At Mt. Zion, McKinney established numerous programs that assisted the black community including the Mount Zion Baptist Church Credit Union in 1958, the first Protestant credit union in the state of Washington. McKinney was a founder of Liberty Bank, the first black-owned bank in Seattle and was the first black president of the Church Council of Greater Seattle.

By the 1960s McKinney became one of the most powerful voices for civil rights in Seattle, participating in demonstrations for equality in housing, employment, and education. He also played major role in the local Central Area Civil Rights Committee. In 1961 Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. made his only visit to Seattle, at the invitation of McKinney. In 1965 McKinney joined in the Selma to Montgomery Voting Rights march which pressured the U.S. Congress to enact the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Continuing his activism into the 1980s, Rev. McKinney was arrested in 1985 protesting apartheid at the South African consul’s home in Seattle. He later chaired the Washington State Rainbow Coalition.

Dr. Samuel Berry McKinney died in Seattle, Washington on April 7, 2018. He was 91 at the time of his death. (www.blackpast.org)

Otis MOSS, Jr. — Fall 1955

Theologian, pastor, and civic leader the Reverend Dr. Otis Moss, Jr. is one of America’s most influential religious leaders and highly sought-after public speakers. A native of Georgia, Moss was born on February 26, 1935, and was raised in the community of LaGrange. The son of Magnolia Moss and Otis Moss, Sr., and the fourth of their five children, he earned his B.A. degree from Morehouse College in 1956 and his masters of divinity degree from the Morehouse School of Religion/Interdenominational Theological Center in 1959. He also completed special studies at the Inter-Denominational Theological Center from 1960 to 1961 and earned his D.Min. degree from the United Theological Seminary in 1990.

From 1954 to 1959, Moss served as pastor of the Mount Olive Baptist Church in LaGrange, Georgia. From 1956 to 1961, he also served as pastor of Atlanta’s Providence Baptist Church and therefore, simultaneously led two congregations from 1956 to 1959. From 1961 to 1975, he pastored the Mount Zion Baptist Church in Lockland, Ohio, and in 1971, he served as co-pastor, with Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Sr., at Ebenezer

Baptist Church in Atlanta. In 1975, he was called to pastor Olivet Institutional Baptist Church in Cleveland, Ohio, where he continues today.

Moss has been involved in advocating civil and human rights and social justice issues for most of his adult life. Having been a staff member of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., he currently serves as a national board member and trustee for the Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Non-Violent Social Change. His work in the international community has taken him to Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Japan as a member of a clergy mission in 1970, and to Israel in 1978. In 1994, he was the special guest of President Bill Clinton at the peace treaty signing between Israel and Jordan, and, in that same year, he led a special mission to South Africa.

Moss is the recipient of numerous awards and honors, including Human Relations Award from Bethune Cookman College in 1976, The Role Model of the Year Award from the National Institute for Responsible Fatherhood and Family Development in 1992, Leadership Award from the Cleveland chapter of the American Jewish Committee in 1996, and an Honorary Doctor of Divinity from LaGrange College in 2004. In 2004, he participated in the Oxford Round Table in Oxford, England, and was a guest presenter for the Lyman Beecher Lecture series at Yale University. (www.TheHistoryMakers.org)

Wiley Abron PERDUE — Fall 1954

Wiley A. Purdue '57 was acting president of Morehouse from October 1994 through August 1995. He also served as the registrar and the vice president of business and finance during a tenure at Morehouse which lasted for 32 years. Dr. Wiley A. Perdue passed away Sunday, October 1, 2017. He was born May 11, 1935 in Jones County, Georgia to the late Augustus George Perdue Jr. and Tommie C. Perdue.

While working at Savannah State, Perdue was approached by then Morehouse President Hugh M. Gloster about returning to his alma mater in the business office. He joined the Morehouse staff as registrar in 1969. He rose through the ranks at Morehouse, becoming the vice president of business and finance before almost a year-long stint as acting president in 1994. He led the university from Oct. 1, 1994, to Aug. 13, 1995, between the tenures of presidents Leroy Keith and Walter Massey.

Constructed in 1996 to accommodate the Centennial Olympic Games in Atlanta, Wiley A. Perdue House is home to approximately 200 upperclassmen residents. With three floors of traditional occupancy rooms, each room is spacious. Study rooms on each floor and a vibrant

community lounge are utilized to host social events. Aligning with our vision of providing a “Premier Residential Experience” in each residential community, residents of Perdue House will experience a host of dynamic programming, community building, and personal development, tailored to the appreciation of art and culture.

Joe Samuel RATLIFF — Fall 1969

Reverend Dr. Joe Samuel Ratliff is a native of Lumberton, North Carolina; where in 1962, he began his Christian journey with Mt. Sinai United Holy Church of Lumberton. Seven years later, he answered his call to ministry while attending Morehouse College. He served as pastor of the Cobb Memorial United Holy Church in Atlanta, Georgia for eight years.

Dr. Ratliff was elected as pastor of Brentwood Baptist Church of Houston, Texas, in February 1980, and by the year 2000, it had grown from a 500-member congregation to a mega-church of 12,000. The congregation has reached a plateau of more than 7,000 members with over 5,000 worshipers attending its two Sunday morning worship services.

Dr. Ratliff has distinguished himself as a scholar-pastor in the African-American tradition of preaching and has sought excellence in numerous endeavors. He has a bachelor’s degree in history from Morehouse College, Atlanta, Georgia, a Master of Divinity degree earned in 1975 and Doctor of Ministry degree earned in 1976 from the Interdenominational Theological Center (ITC), Atlanta, Georgia. He received an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree, also awarded by ITC. He has done Post-Doctoral work at Harvard Divinity School as a Charles Merrill Fellow.

Dr. Ratliff is the first African American pastor to lead the Union Baptist Association, the largest urban Southern Baptist organization in the United States representing more than 500 churches and missions. He has been named “Minister of the Year” by the National Conference of Christians and Jews and is founding president of the National African-American Fellowship of the Southern Baptist Convention.

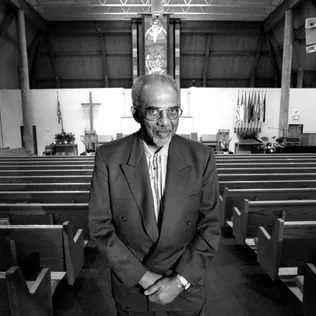

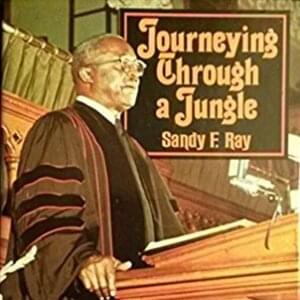

Sandy Frederick RAY — Fall 1926

Named by Brother Martin Luther King, Jr. as one of the strongest orators in the African American church, Sandy Ray was one of many talented ministers who, through his association with Martin Luther King, Sr., served as a role model for King, Jr.

Born in Texas, Ray was King, Sr.,’s closest friend while they attended Morehouse College’s three-year minister’s degree program. After graduating in 1930, Ray served Baptist churches in LaGrange, Georgia; Chicago, Illinois; Columbus, Ohio; and Macon, Georgia, before being called to Brooklyn, New York’s Cornerstone Baptist Church in 1944, where he served as pastor until his death. Ray was one of six candidates nominated for president of the National Baptist Convention in 1953.

Beginning in 1954, he presided over New York’s Empire Missionary Baptist Convention for many years.

Throughout his life, Ray remained close to the Kings. King, Jr., remarked during a March 1956 speech in New York, “I’m glad to see Rev. Sandy Ray out there.… You know, for years he was ‘Uncle Sandy’ to me. In fact, I did not know he was not related to me by blood until I was 12 years old” (Herndon, “Sidelights of a ‘Kingly’ Meeting”). Earlier in the month Ray had attended a Montgomery Improvement Association mass meeting in support of the Montgomery bus boycott. It was at Ray’s parsonage at Cornerstone Baptist that King recuperated after being stabbed in September 1958 by Izola Ware Curry.

Ray supported the efforts of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference by serving as a member of the steering committee for a June 1961 fundraising effort in New York City. He was also a founding member of the board of directors of the Gandhi Society for Human Rights. On the afternoon that Ray dedicated Cornerstone Baptist’s community center in 1966, King delivered the sermon “Guidelines for a Constructive Church” there. Ray delivered the eulogy at the funeral of King’s mother, Alberta Williams King, in 1974. (The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University)

John "Jack" Henry RUFFIN, Jr. — Fall 1955

By the time John H. "Jack" Ruffin Jr. became the first African-American chief judge of the Georgia Court of Appeals, he had been a pioneering civil rights lawyer who integrated the Augusta school system and a distinguished jurist for two decades.

Mr. Ruffin, who retired from the Court of Appeals at the end of 2008, died Friday at age 75 after collapsing at his home in Atlanta. Mr. Ruffin became a lawyer against his mother's wishes. She wanted him to be a schoolteacher, thinking he would be put in harm's way as a black lawyer in the Deep South in the 1960s. Mr. Ruffin did have some close scrapes. On one occasion, he found himself jailed for contempt in Waycross after a contentious cross-examination of then-Sheriff Robert E. Lee, who told Mr. Ruffin to stop pointing his finger at him.

After Mr. Ruffin won an acquittal for a black client who was accused of raping and killing a white woman, a Hart County judge ordered a deputy to escort the lawyer until he was safely across the county line. Three years into his legal career, Mr. Ruffin shook up Augusta's white establishment by filing suit to desegregate the Richmond County school system. He doggedly pursued the litigation for decades against a defiant school system and hostile judges before finally obtaining a federal court order to integrate the system. Throughout the contentious litigation, Mr. Ruffin was always ethical and professional -- "a perfect gentleman," U.S. District Judge Anthony Alaimo said in an interview before he died in December.

Mr. Ruffin was the first black member of the Augusta Bar Association, which waited 10 years after he set up practice before extending him an invitation. He was the first black Superior Court judge in Augusta. And, in 2005, he became the first black chief judge of the state Court of Appeals. At the time of his death, Mr. Ruffin held a position teaching a class at Morehouse College. (Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Feb 1, 2010)

Willis Braswell SHEFTALL, Jr. — Fall 1961

Inside the Office of Academic Affairs, there are three rows of photos of all of the past provosts for the College. The last one is of Willis B. Sheftall Jr. ’64. Had he had his way, Sheftall’s photo never would have been there. “If you had asked me when I was coming here whether I wanted to be an administrator or not, I would have said ‘no’” he said. “I wouldn’t have been hesitant about that. It just wasn’t an aspiration that I had.”

Having three times served as Morehouse’s provost (1999 to 2005; 2007-11 and 2012-13) and once as acting president (2013), Sheftall now sees his move into administration as answering his alma mater’s call to service, for which he says he has always been proud to do. Sheftall has long been a respected economist with a particular interest in the economics of higher

education, local public finance and U.S. economic history. He’s served on boards of institutions such as Fisk University, American Assembly of Collegiate Schools of Business, Junior Achievement of Georgia, Atlanta’s Piedmont Hospital, and SOLINET (Southeastern Library Network). He also served on the Atlanta Mayor’s Council of Economic Advisors.

He taught at Alabama State University and Georgia State University before returning to his alma mater to teach in 1974.

He became chairman of the department of economics at Hampton University in 1981 and later dean of Hampton’s School of Business. Sheftall returned to the classroom in 1986 when he came back to Morehouse as a professor of economics, and also as the Charles Merrill Chairman of the department of economics.

Along with first becoming provost in 1999, he also served in other administrative capacities at the College, including special assistant to the president with oversight responsibilities for institutional advancement and budgeting.

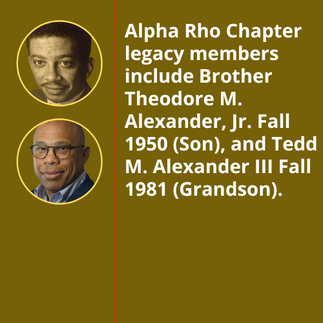

No matter what he was doing, student development remained a primary focus for Sheftall. Teaching is the first love for the Macon, Ga., native. “Watching young men develop into full manhood is one of the truly exciting experiences that you have here at Morehouse,” he said. “I have now almost third-generation students. I have the father whom I taught and then the son, and now I have the grandson. Certainly, I have the grandsons or grand nephews of classmates I was in undergraduate school with. That’s what I’m going to miss – the day-to-day interaction with these young guys and watching them grow up.”

For a pragmatic academic, even Sheftall admits there is some undefined part of the Morehouse experience that has made his time at the College special. “I’m a hard-boiled economist,” he said. “I’m not one of those people who believes a lot in mystery. But there is some magic that occurs here. We can talk about what we do with respect to 90 percent of the experience a student has here. We can say this is what he’s doing. He takes this course; this is the outcome we expect. But it’s about 10 percent magic. That’s the mystique. That’s critical. It’s not just the icing on the cake. It’s more like the icing throughout the cake. That Morehouse mystique is real, and I think its one of the things that sets us apart.” (Morehouse Magazine Commencement 2013 / Commemorative Issue)

Kelly Miller SMITH — Spring 1939

Kelly Miller Smith (1920-1984) was a clergyman and civil rights activist in Nashville. He earned a Bachelor of Divinity degree from Morehouse College and a Master of Divinity degree from Howard University. He came to Nashville's First Colored Baptist Church in 1951, and served as the president of the Nashville chapter of the NAACP.

In 1955, he and twelve other African American parents filed a federal lawsuit against segregation in the Nashville public schools. In 1958, he founded the Nashville Christian Leadership Council. He played an important role in the Nashville sit-in movement in the early 1960s. He served as Assistant Dean of Vanderbilt University's Divinity School from 1969 until his death.

Smith moved to Nashville, Tennessee, in 1951 where he became pastor of First Baptist Church, Capitol Hill, a post he would retain until his death in 1984. He became president of the Nashville NAACP in 1956 and founded the Nashville Christian Leadership Council (NCLC) in 1958. Through the NCLC, Smith helped to organize and support the Nashville sit-ins — a movement which would successfully end racial segregation at lunch counters in Nashville.

In a 1964 interview with Robert Penn Warren for the book Who Speaks for the Negro?, Smith comments that the end to segregation was achieved through much hardship and many negotiations by the NCLC.

In 1969, Smith became assistant dean of the Vanderbilt University Divinity School. He was the first African American to become a faculty member in the school.In 1994, the Jefferson Street bridge in Nashville, Tennessee, was renamed and dedicated to honor the Rev. Kelly Miller Smith. Smith died of cancer on June 3, 1984. (www.vanderbilt.edu)

Otis Wesley SMITH — Spring 1946

It's one of the city's most striking examples of paying it forward. When Atlantans rallied to save the historic Margaret Mitchell house, Dr. Otis W. Smith led the charge. "Our first donation to save the house came from him, unsolicited," said Mary Rose Taylor, founder of the Margaret Mitchell House and Museum. "He wrote a check for $10,000 and just showed up with it." He went to Germany to drum up Daimler-Benz funds for the museum, talked up the project constantly and stopped by often to greet visitors, Mrs. Taylor said.

In his mind, Dr. Smith was simply repaying a debt. In medical school, he was so poor that he almost dropped out until his mentor, Dr. Benjamin E. Mays, then Morehouse College president, interceded. Suddenly, the funds were there.

Only later did Dr. Smith discover he was one of at least 40 Morehouse graduates to receive anonymous scholarships from the "Gone With the Wind" author --- money that allowed them to attend medical school. If not for Margaret Mitchell, "I wouldn't be a doctor and I wouldn't be what I am today," Dr. Smith said in a 1998 Atlanta Journal-Constitution article. "She didn't want anybody to know that she was doing this, but she was concerned about blacks getting medical care."

Dr. Smith adopted that same cause as his personal mission, often in the same anonymous way. Recognized as Georgia's first certified black pediatrician, he funded Morehouse scholarships. With a group of civil rights activists and other medical professionals, he fought to desegregate hospitals in Atlanta and across the country. "Giving back to the community, that's what he preached all the time," said his wife, Gwendolyn Smith of College Park. "Whenever he met with young people, he said, 'Get yourself prepared and then go back to your community and help bring somebody forward.' "

Dr. Otis Wesley Smith, 81, of College Park died of complications from Alzheimer's disease Feb. 5 at South Fulton Medical Center. The funeral is noon Monday at Morehouse College's Martin Luther King Jr. International Chapel. Sellers Bros. is handling arrangements.

The Atlanta native vowed to become a doctor when his father died from inadequate care. Dr. Smith received a BS degree from Morehouse College in 1947, where as "Will Shoot" he was the only documented athlete to letter in four varsity sports; that record still stands. After graduating in 1954 from Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tenn., he practiced medicine in Fort Valley. His outspoken nature surfaced there, when he barely escaped jail time for talking back to a white woman who used a racial epithet toward him. His gentler side surfaced at his downtown Atlanta pediatric practice, where he treated generations of patients from 1964 to 1987. Tall and athletic, he was quick to smile and quick to tip his hat, Mrs. Taylor said.

At its best, Dr. Smith's life as an activist and former NAACP Atlanta branch president brought him more honors than he could display. At its worst, it led to death threats. "When I first met Otis, he seemed like a calm, logical, reasonable man," said Xernona Clayton, president and CEO of the Trumpet Awards Foundation. "But if you didn't get his message, he got a little agitated and it showed in his voice." "He could be pretty spicy and feisty, but there was always a smile," said Ms. Clayton of Atlanta. "He had the warmest-looking countenance, and I would tell people, 'Don't be fooled by that if you ruffle his feathers.' "But he fought injustice wherever it raised its ugly head," she said. That struck her full force when she visited him in a hospital room that was not at Grady Memorial Hospital.

Before desegregation, Ms. Clayton said, "blacks had to go to Grady. They didn't have a choice." "When I walked in the room and saw him lying in the bed, I realized he'd made that choice possible --- for himself and for others."(Holly Crenshaw, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, February 11, 2007)

In 2017, Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed, Commissioner Amy Phuong, Department of Parks and Recreation staff, Atlanta City Councilmember C.T. Martin, community leaders and family members of doctors who practiced at Southwest Hospital joined together on Nov. 22 to celebrate the opening of the new Doctors Memorial Park in Southwest Atlanta. The park, at

500 Fairburn Road SW, is named in honor of the historic Southwest Hospital, formerly named Holy Family Hospital and the doctors who played a vital role in providing healthcare and supporting the wellbeing of the community. (National Park Service International Civil Rights Walk of Fame)

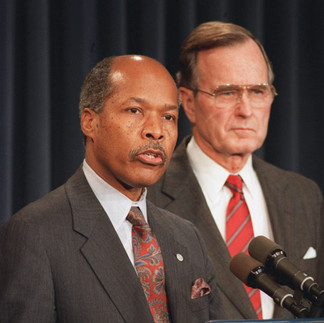

Louis Wade SULLIVAN — Fall 1951

Federal cabinet appointee and college president Dr. Louis Wade Sullivan was born on November 3, 1933, in Atlanta, Georgia, to Lubirda Priester and Walter Wade Sullivan. After graduating from Booker T. Washington High School, Sullivan received his B.S. degree in biology in 1954 from Morehouse College. He received his M.D. degree in 1958 from Boston University School of Medicine, completing his residency two years later at New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center.

In 1960, Sullivan began a one-year pathology fellowship at Massachusetts General Hospital, in Boston, before working at Boston City Hospital and studying hematology at Harvard Medical School’s Thorndike Memorial Laboratory until 1963. He was hired as co-director of hematology at Boston University Medical Center in 1966 and he founded the Boston University Hematology Service in 1967.

In 1975, the Morehouse College Medical Education Program was founded and Sullivan returned to Atlanta to serve as its first dean and director. The Program became The School of Medicine at Morehouse College in 1978. In 1981, the School became independent and was re-named Morehouse School of Medicine (MSM)—the only predominantly black medical school in the United States established in the twentieth century—with Sullivan serving as its founding president and dean. In 1989, Sullivan left MSM to accept an appointment from President George H. W. Bush to serve as Secretary of the United States Department of Health and Human Services. Sullivan returned to MSM in 1993 as president, becoming president emeritus in 2002.

In 1976, Sullivan became founding president of the Association of Minority Health Professions Schools and, in 1985, he became one of the founders of Medical Education for South African Blacks, serving as chairman from 1994 to 2007. From 2001 until 2006, he served as co-chair of the White House Commission on HIV and AIDS. In 2003, he was appointed chair of the advisory committee of the White House Initiative on Historically Black Colleges and Universities. Sullivan also has served as co-chairman of the Henry Schein Cares Foundation, chairman of the Washington, D.C.-based Sullivan Alliance to Transform the Health Professions, now a central program of the Association of Academic Health Centers (AAHC), and on the boards of 3M, United Therapeutics, Emergent BioSolutions, General Motors, Cigna, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Equifax.

Sullivan has received more than seventy honorary degrees, including an honorary M.D. degree from the University of Pretoria in South Africa. He was the 2008 recipient of the Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter Award for Humanitarian Contributions to the Health of Humankind from the National Foundation for Infectious Disease. (www.TheHistoryMakers.org)

Wendell Phillips WHALUM, Sr. — Fall 1949

Musician, composer, educator. Legendary director of the Morehouse Glee Club and the Head of Music at Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia. A giant in the area of chorale music who brought the Morehouse Glee Club to international prominence as its director for more than 30 years. He, also created an immense variety of musical arrangements and published numerous articles and chapters in books. His well-known compositions include "Guide My Feet," "I'm Gonna Live So God Can Use Me," "The Lily of the Valley," "God Is A Good God," and "Sweet Jesus."

He is also uncle to well-known jazz sax man Kirk Whalum. His musical talent, which was evident, was nurtured at a young age by his parents. Whalum graduated from Booker T. Washington High School in Memphis, Tennessee and entered Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia. He received the Bachelor of Arts degree from Morehouse College in 1952, the Master of Arts degree from Columbia University in 1953, and the Doctor of Philosophy degree from the University of Iowa in 1965. The University of Haiti conferred upon him the Doctor Honoris Causa in 1968.

After joining the faculty of Morehouse College in the fall of 1953, Dr. Whalum was appointed Director of the Morehouse College Glee Club, which earned national and international acclaim during his 30 plus years of leadership. In spite of numerous offers of positions at major college and universities, he chose to remain at Morehouse where he spent his entire professional career and achieved an enviable record as a professor, director of Band and Glee Club, Chairman of the Music Department, and Fuller E. Callaway Professor of Music. He was elected Faculty Representative to the Morehouse Board of Trustees and the National Alumni Association.

He was also a Merrill Faculty Travel-Study Grant Abroad recipient and a Danforth Fellow. Whalum achieved international recognition as teacher, organist, conductor, musicologist, arranger, composer, author and lecturer; and he traveled extensively throughout the United States and abroad. He performed with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra as an organ soloist in 1968, and he prepared the chorus for the world premiere of the opera in 1972. During that same year, he took the Glee Club on a State Department tour of five countries in West and East Africa. He also prepared the Morehouse College Glee Club and the Atlanta University Center Community Chorus for numerous appearances with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, and he conducted at major music centers, including the Lincoln Center and the Kennedy Center.

Through his involvement in and contributions to the community, he reached legendary fame. He organized and directed the Atlanta University Center Community Chorus (now The Wendell P. Whalum Community Chorus) and co-directed the Morehouse-Spelman Chorus. Because he was always extremely interested in quality church music, he accepted positions as organist-choirmaster for several Atlanta churches. He was constantly selected as a music consultant, as a member of evaluation committees, as a conductor or workshops, and as a lecturer throughout the United States and abroad.

He held memberships on advisory boards of numerous music and civic organizations. He was a member of Phi Beta Kappa, Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia, American Guild of Organists, National Humanities Faculty, National Society of Literature and the Arts, Music Educators National Conference, Georgia Folklore Society, Alpha Phi Omega Service Fraternity, Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, and the Intercollegiate Musical Council. In 1982, the Wendell P. Whalum Organ in the Martin Luther King, Jr. International Chapel at Morehouse College was dedicated to him. Whalum died at age 55 from a heart attack. (Custis Jackson)

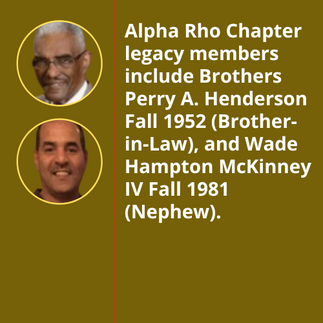

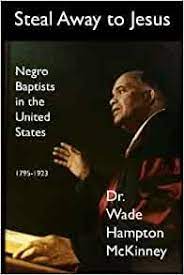

Wade Hampton McKINNEY —

Reverend Wade Hampton McKinney (1892-1963) distinguished himself both in religious and civic affairs. He is the Grandfather of Bro. Wade Hampton McKinney IV (Fall 1981). Rev. McKinney was born in White County, Georgia, on July 19, 1892 to Wade and Mary B. McKinney, and attended Atlanta Baptist College Academy, Morehouse College, and the Colgate Rochester Theological Seminary. His education was interrupted for a year while he served in the United States Army during World War I. Upon his return, he completed his education at Morehouse College.

In 1923, after graduating and obtaining his degree from Colgate Rochester Seminary, Reverend McKinney became the pastor of Mount Olive Baptist Church in Flint, Michigan. During his ministry there, he married Annie Ruth Berry. Also while in Flint, two sons, Wade Hampton III and Samuel Berry, were born. Twin daughters, Virginia Ruth and Mary Louise, were born in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1932.

In 1928, at the age of thirty-six, he was asked to come to Cleveland, Ohio, to become the seventh pastor of Antioch Baptist Church. Under his leadership, the membership of Antioch, then located at East 24th Street and Central Avenue, grew from approximately 700 to more than 3,000. In 1945, Reverend McKinney organized the Credit Union which grew to become the largest Protestant Credit Union in Ohio, boasting assets of more than $360,000.00. As the need for a new church location became necessary, he led the congregation to its present site at East 89th Street and Cedar Avenue. An ever increasing membership led to the dedication of the "McKinney Youth Center" in 1959. The unit includes a recreational hall, a nursery, twenty-two classrooms, a projector room, and library space.

Reverend McKinney participated in both local and national church organizations. He served as President of the Cleveland Baptist Association and the Cuyahoga Interdenominational Ministerial Alliance. He was a member of the Board of Directors of the Cleveland Area Church Federation. In 1947, he attended the Baptist World Alliance in Copenhagen, Denmark, and in 1955 he was a delegate to the 50th Baptist World Alliance in London, England. Shortly afterwards, he attended the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) Centennial in Paris, France.

His services and ministry extended far beyond the work of his church. He was active in many of the social and civic agencies which concerned the welfare of Cleveland and he worked with several business enterprises designed to increase the economic status of poor people.

Reverend McKinney was one of the founders of the Future Outlook League which opened many jobs formerly closed to African Americans. He helped organize the Cleveland Business League and the Mt. Pleasant Community Council. During World War II he served on Selective Service Board number 19. Reverend McKinney was a member of the Budget and Policy Committee of the Welfare Federation of Cleveland. He helped organize the Quincy Savings and Loan Company and was the founding force behind the Forest City Hospital. Many successful voter registration campaigns were led by Reverend McKinney. He served on the Mayor's Committee under Mayor Frank Lausche. Also, Reverend McKinney was a member of the Board of Directors of the Cedar Branch of the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA), serving most of the timie as chairman and a trustee of the Metropolitan YMCA. Reverend McKinney holds the honor of being the first African American foreman of the Cuyahoga County Grand Jury. It was during his term that a crusade against gambling was launched.

Wade Hampton McKinney died in Cleveland, Ohio, on January 18, 1963, after serving as pastor of Antioch Baptist Church for over thirty-four years. (Western Reserve Historical Society)

Comments